Oil based insights from ga$ price$

Prime Future 104: the newsletter for innovators in livestock, meat, and dairy

This April headline caught my eye:

Although it’s a bit dated now since oil prices are back up, the article is still relevant as it answers the question by looking at the structure and complexity of the value chain.

"Oil prices have tumbled almost 20% from a multiyear peak in March, but the prices American drivers are paying at the pump are still hovering around record levels.

The difference between the costs of oil and gasoline has attracted attention from politicians, some of whom have accused oil companies of price gouging, as U.S. inflation soars.

Oil prices have in fact been falling more quickly than gasoline prices. Oil was at $100.60 a barrel Tuesday, down about 19%

from an almost 14-year peak in early March, while a gallon of regular gas averaged about $4.098 on Tuesday, only about 5.4% lower than the all-time record in March.But the system that turns oil into gas in the U.S. is big, complex and not controlled by any one company. Thousands of companies drill for oil. Dozens refine that oil into fuel. And tens of thousands of largely independent gasoline stations sell that fuel to customers."

Of course this is all interesting because holy ga$ price$ 😵💫, but mainly because of its parallels to price chaos across protein value chains over the last couple of years with both live animal prices and meat and milk prices.

Maybe there are some oil based insights that are relevant for livestock?

To explore that, let’s start by comparing the structure of oil with a protein value chain - let’s use beef. Full disclosure we are going to hunt for insights by oversimplifying things; you’ve been warned.

The article explains the gasoline value chain like this:

~9,000 companies drilling for oil

129 companies refining the oil

~130,000 (mostly independent) gas stations selling gasoline

Contrast that with the beef value chain:

~900,000 cow-calf producers selling calves

~300,000 stockers selling feeder cattle

~26,000 feedyards finishing cattle

~80% of cattle processed by 4 packers selling meat into export, foodservice & retail channels

~63,000 grocery stores who sell to meat eaters (but a way smaller # of chains, obvs)

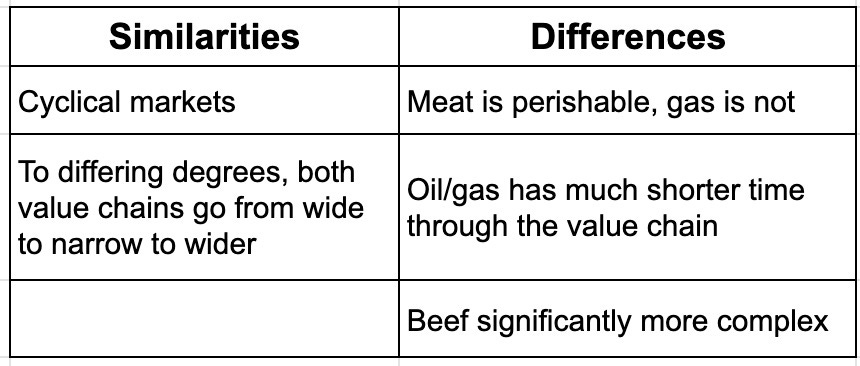

Even though the commodity’s characteristics obviously impact value chain structures, it’s not actually that relevant to our ‘so what’ today. But here are a few similarities and differences in oil/live cattle and gasoline/meat:

With that context, now to the good part!

"When gas station owners buy more expensive fuel, they typically wait two to four days to start substantially raising pump prices because they are reluctant to lead the market in price increases. When oil prices decline, gas station owners also tend to follow more slowly, with pump prices floating down “like pigeon feathers,”...."

Implicit in this paragraph is the idea that these independently owned gas stations do not have the ability to systematically manage price risk other than the timing of changing retail prices which is in a wickedly competitive market since there’s a gas station or 10 on every corner. They are exposed to market risk both in how they buy and how they sell.

But if live cattle is oil & meat is gasoline, we run into a narrative violation.

Many would say that live cattle prices are low and meat prices are high because of concentration among the packers. But in the oil & gas scenario, refining is also fairly concentrated yet gas prices remain high because of fragmentation at gas retail. Wait…concentration or fragmentation can cause market funkiness?!

Whether gasoline or feeder cattle, buying or selling a commodity inherently includes price risk. As a seller, the more you identify as a price taker the more price risk you are exposed to. Duh.

But larger organizations tend to have the capability to better manage risk, from the sophistication and know how to create risk management *strategies* to the systems that help execute risk management *tactics*. It tends to be the smaller players that absorb the price uncertainty because they tend to have less resources and capability and so are less likely to manage risk.

(Obviously there are outliers - I see you.)

The ‘so what’ is that regardless of what commodity you are in the business of producing/processing, at the extremes there are 3 options:

Swim in the sea of commodity price risk. Ride the wave of profit in, and the wave of loss out, expecting the waves to be favorable over the long run.

Get really really good at managing price risk from strategies and tactics to systems and discipline.

Channel your inner fairlife milk / Eggland’s Best eggs / Snake River Farms beef to get as far out of commodity markets as you can by positioning yourself in non-commodity markets. Or at least in markets that are less commodity-ish.

None of those are right or wrong. Empires have been built from all 3 options….and empires have been lost from all 3.

None of those 3 are necessarily exclusive - many successful businesses have built the even more impressive capability of knowing when and how to use all 3. Meta.

I have a regular debate with a friend about whether it’s better to be in a low margin high volume business or in a lower volume higher margin business. Of course it comes down to two assumptions:

(1) this is a ‘different strokes for different folks’ kind of question which includes personal preferences and capabilities and resources.

(2) the key to make low margin high volume work is to lower volatility and lessen the impact of cyclicality - however you make that happen. Whether it’s through flexing capacity, a financial hedge, long term supply agreements, some other strategy, or the systematic combination of multiple strategies.

My aha from comparing meat and oil is that lessening the impact of market cyclicality is basically the business of production - wherever you are in the value chain, whatever value chain you are in.

I come back to this topic somewhat frequently for a few reasons:

Because sometimes people who work around agriculture but not in production fail to appreciate what it’s like to operate in a commodity market. Spoiler alert: it’s hard.

I love talking to super successful producers because they inevitably have simultaneous strong conviction and hard won humility about this topic because they have built a systematic approach to managing market risk - whether it’s being fully exposed to the market to capture the upside of the good years by having enough equity to ride out the bad years, or whether it’s creating brands to get out of the commodity category, or laser focusing on having the lowest cost of production.

Who knows what gas prices will do over the next 2 years. But if we’re going to pay out the nose we’re at least gonna try to learn something from it, amirite? Especially if it’s true that oil and cattle have more in common than the Permian Basin. 😉

What aha’s does the oil:cattle and gasoline:meat analogy bring to your mind?

I don’t wanna feed the world anymore. (link)

Last week we looked at the flaws in the oversimplified and overuses industry cry of ‘feed the world.’ I was under the impression that this really started after the 2009 FAO report, but several readers pointed out that this was really more of an outgrowth of Norman Borlaug’s incredible work in wheat breeding and the Green Revolution.

Thank you to those who shared the earlier origins of ‘feed the world’ but I’m bummed I missed an opportunity to talk about Norman! To be remedied eventually.