Love Me Tenders: a supply chain story

Prime Future 71: the newsletter for innovators in livestock, meat, and dairy

New to Prime Future? Welcome! Subscribe to get weekly content in your inbox.

“There does not seem to be any relief on the horizon.”

Supply chain: the red headed step child of business school disciplines; the silent function that just effortlessly does its thing; the heartbeat keeping blood (stuff) moving through the body (economy) without a second thought required.

Or at least that's how it seemed until we started seeing signs like "due to supply chain shortages, we are out of guacamole and Ford F-250's."

Supply chains are in the spotlight now, as they have been since toilet paper-gate began in March 2020.

As we kick off this series on how supply chain disruptions & dynamics are impacting meat & poultry and how this could play out in the future, today we'll look at 2 macro concepts, what’s happening in milk hauling, and a chicken tender supply situation.

Supply Chain Inception

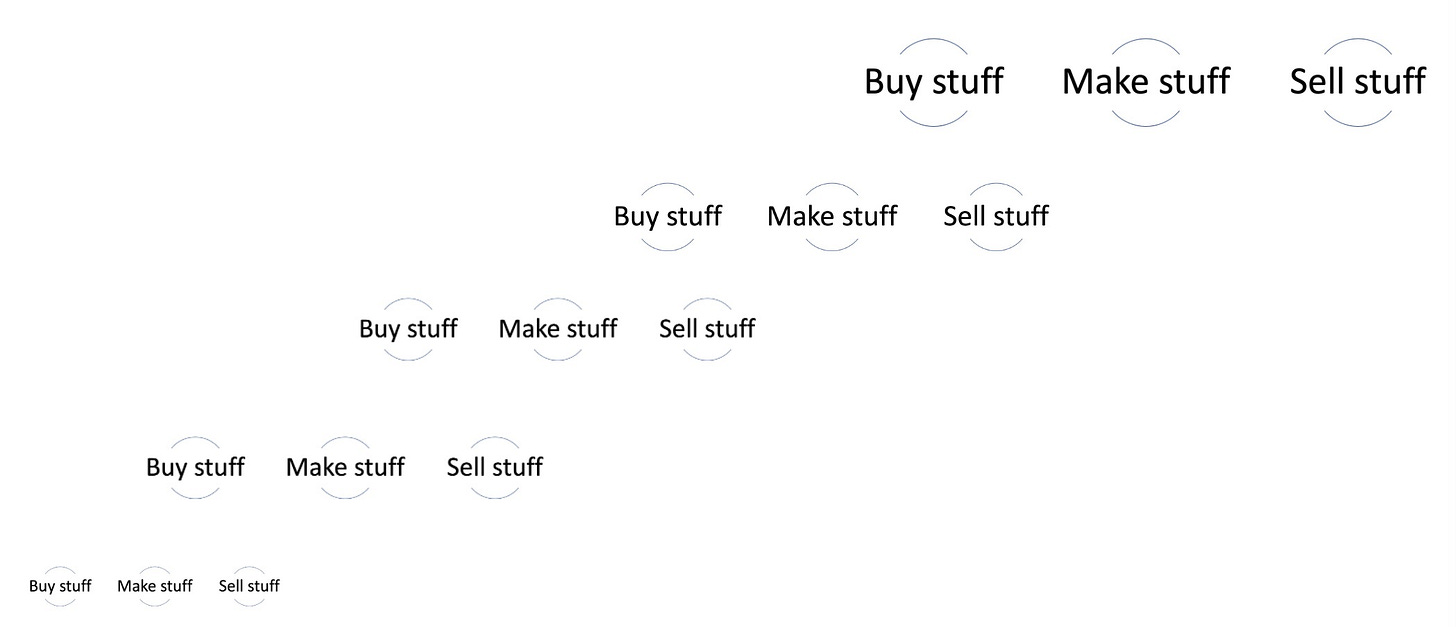

Every company buys stuff to make stuff to sell stuff, which is a simplified version of Wikipedia's definition of a supply chain as "a system of organizations, people, activities, information, and resources involved in supplying a product or service to a customer."

So we start with Company A’s supply chain, who buys inputs from Company B who buys inputs from Company C and so on and so on. Suppliers are dependent on their suppliers to provide inputs; customers are dependent on supply chains to function. The layers keep pulling back like some sort of supply chain inception:

Sometimes the supply chain inception is called The Global Supply Chain, a generic term being thrown around a lot right now that may or may not be relevant. No one cares about THE supply chain, they care about disruptions to MY supply chain.

In theory vertical integration solves some of this, but not entirely. More on that in a moment…

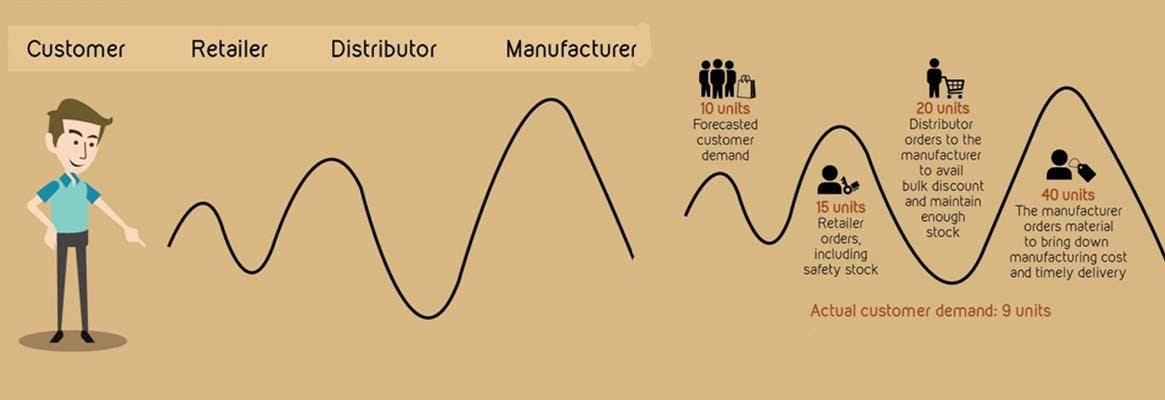

Supply Chain Chaos: The Bullwhip Effect +

"The bullwhip effect is a supply chain phenomenon describing how small fluctuations in demand at the retail level can cause progressively larger fluctuations in demand at the wholesale, distributor, manufacturer and raw material supplier levels. The effect is named after the physics involved in cracking a whip."

For a lot of companies, the 2020 demand increase didn't start until a little ways into the pandemic, maybe even after the first stimulus check. But for meat companies it was immediate in March as the ~50% of total meat sold through foodservice shuttered and shifted to retail, where grocery store shoppers stocked up for what felt at the time like the looming apocalypse, emptying the meat case day after day after day.

Simultaneously, getting enough employees to run the plant went from challenging to existentially difficult. I cannot remember a single livestock or meat industry conference that didn’t discuss labor as a critical issue - labor as a challenge is not at all new….what's new is the severity of the issue.

As we know the 2020 Bullwhip effect created huge and harmful waves upstream to livestock producers, especially as it was compounded with a supply constraint and labor shortage. We basically had supply and demand shocks competing with one another, compounded by labor shortage. I picture the hypothetical equation looks something like this:

It’s not hard to imagine this wild combination of competing & simultaneous dynamics will go in supply chain textbooks as the COVID effect…and the effects continue playing out. Truthfully, we don’t actually know how it ‘ends’.

While this isn't the place to hypothesize on labor impacting policies or the root origins of the labor shortage, the fact is that in the United States there are 5 million fewer people in the workplace today than in April 2020. That labor shortage is felt in two key ways:

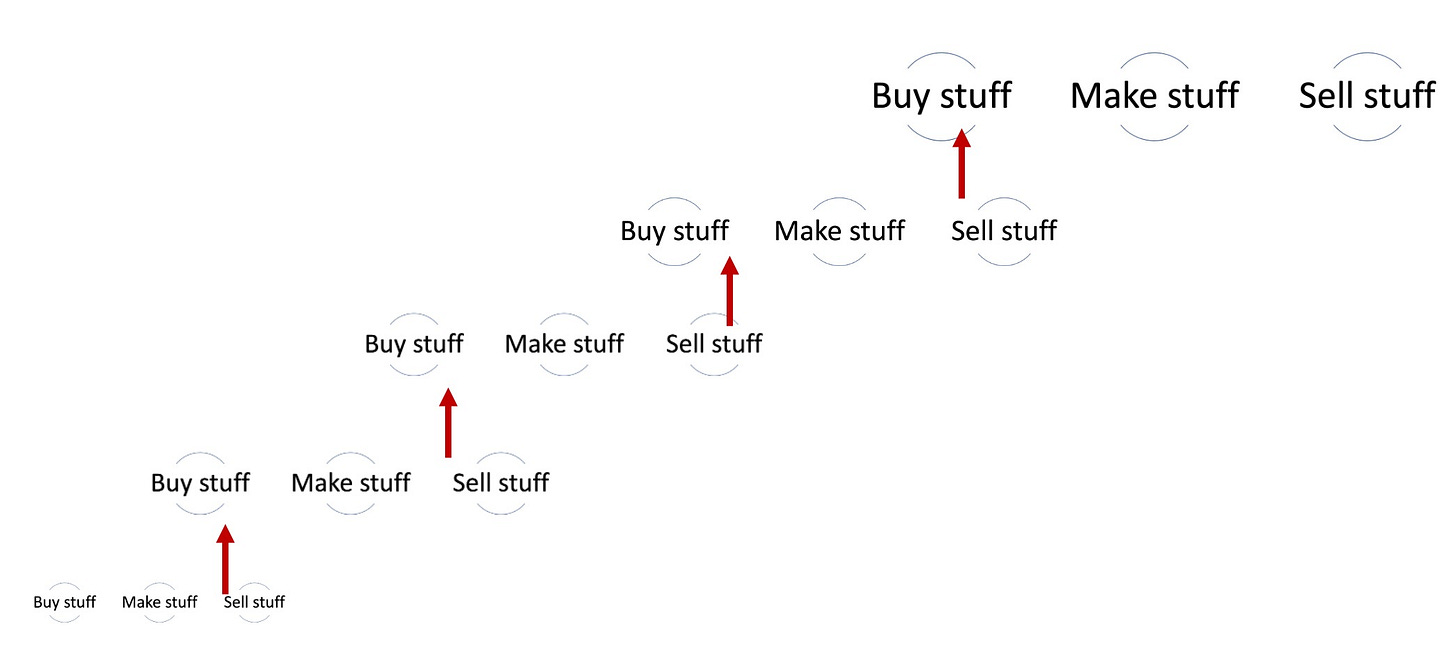

(1) Labor to transport goods. If trucking is a "job of last resort" in a time where people don't need to resort to their last and worst option, well....here we are. Truckers are required in order to move product from Point A to Point B at every transaction, and some in between. The red arrows are red because those are now high risk potential bottlenecks:

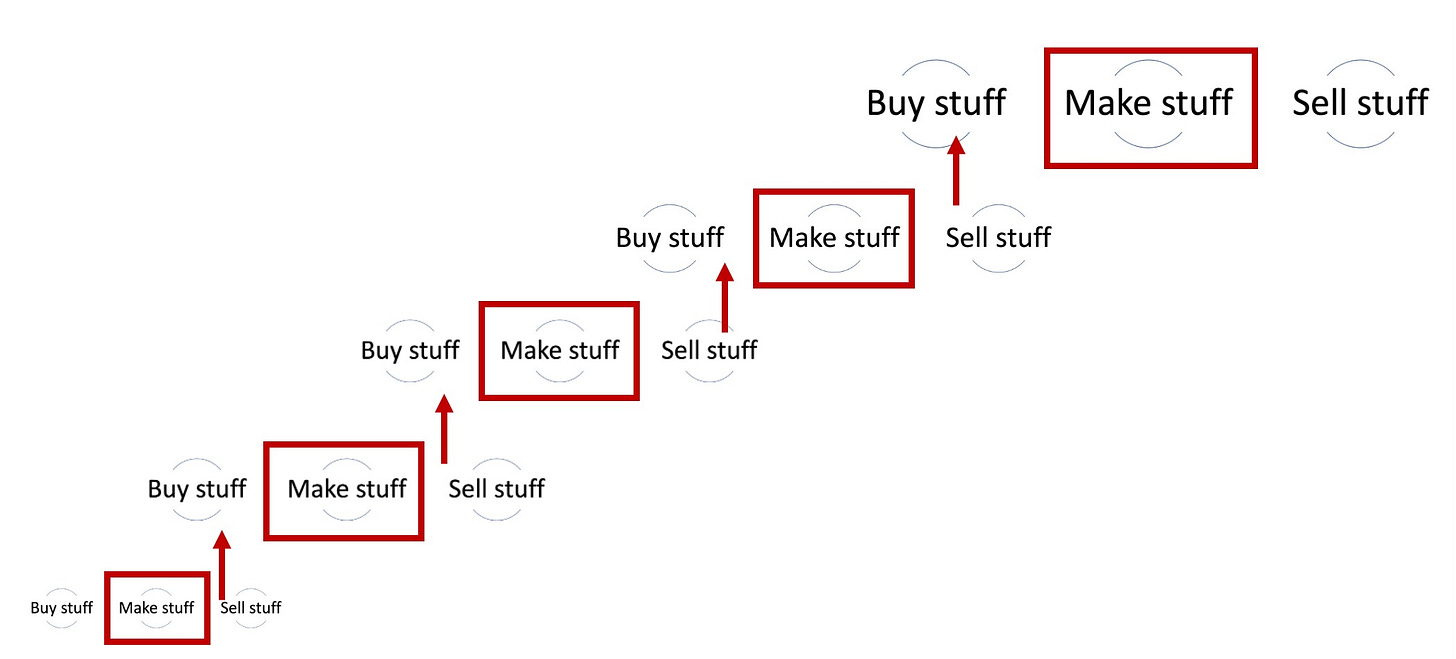

(2) Labor to do the making. If you don’t have labor in the manufacturing plant, you won’t have anything to transport. The red boxes are red because those are also high risk potential bottlenecks:

Plants have struggled to keep the fabrication floor staffed up, often at the expense of further processing capacity which means selling more bone in hams rather than higher value boneless hams, as one example. The Daily Livestock Report provided this commentary on the recently increased volatility of the pork cutout in the US:

“While one can point to a number of factors driving this day to day volatility, we think a major issue has been the widening spread between bone- in and boneless items. The wide spread reflects the impact that limited labor has had on the ability of packers to run boning and trimming lines, be this for hams, loins or other products.”

….and that’s nothing compared to the situation in the UK. According to Bloomberg:

“U.K. farms have begun the daunting task of destroying pigs as worker shortages leave 120,000 animals with nowhere to go, meaning livestock could end up as pet food instead of pork. A worker crunch -- driven by Brexit and the pandemic -- has seen processors cut slaughter rates by as much as 25% since early August.”

People tend to, uh, get grumpy when impacted by shortages, delays, price hikes, or (more likely) some combo of all 3 effects caused by supply chain bottlenecks. Managers & owners want to maximize profit, which they can’t do without being sufficiently staffed. Buyers want predictability of price and availability, which they don’t get on non-existent or delayed goods. Sellers want commissions, which they don’t get on product unavailable to sell.

How is the driver shortage impacting milk hauling?

Hill Pratt, Managing Director of the Transportation Business Unit for Dairy.com provided these astute observations:

“

The driver shortage has become the limiting factor in getting dairy loads moved.Since June of this year, short-notice and weekend loads have become difficult (and at times, impossible) to cover and spot hauling rates have shot up to the highest levels we have ever recorded.Covid has impacted many haulers and some haulers report large numbers of parked trucks due to lack of drivers. Hauling companies have added pay and (especially) benefits to attract drivers and are working hard to accommodate driver lifestyle preferences.

Many dairy haulers feel that drivers are simply not available—at any pay level—in their market areas.Owners of smaller and medium-sized hauling companies are often back to driving trucks on a fulltime basis and see no way to replace drivers who leave.Nearly all hauler input costs—drivers, equipment, parts, tires, insurance and fuel—have spiked in the last couple of years. To avoid maintenance headaches, hauling companies had begun replacing trucks earlier, but with delivery on new trucks ordered today delayed until 2023, hauling companies are forced to keep old trucks in service longer—driving up maintenance costs and downtime (given the shortage of replacement parts).”

On how this situation might evolve in the future, Hill said this:

“There does not seem to be any relief on the horizon. If anything, the capacity crunch that hit the industry this summer may become worse as milk production increases this winter (if it follows typical seasonal patterns.)

Whereas plant processing capacity has historically been the limiting factor (which has caused instances of “dumped milk”), the industry faces the prospect of dairy hauling shortfalls causing milk (and milk components) to build up beyond the capacity to store them. This may force dairy companies to cease production, dump milk products and/or miss/delay orders.”

Ouch.

Love Me Tenders

To continue pulling this thread, let’s take the POV of the head poultry buyer at a fictitious fast food chain, Love Me Tenders. This chain has 10 distribution centers and 2,000+ stores across the country where they sell air fried chicken tenders (and accept only cryptocurrency as payments, but that’s a topic for another day).

The buyer's responsibility is to manage 3 variables while procuring chicken tenders:

Quality - everything coming into the DC & the stores must meet company specs.

Availability - the product HAS to be there or else the company can't make the stuff to sell the stuff to the people who pay the money.

Price - responsibly managing COGS.

(There's a whole discussion to be had about how different procurement organizations think about the prioritization of these 3 variables relative to their business model. For today let's assume that our buyer ranks them in the order above.)

So our buyer calls their 3-5 strategic suppliers. Our buyer has negotiated long term agreements with suppliers in order to manage the 3 priorities above but hey, its 2020-2021 and its the wild west out here…hard to say how well suppliers will be able to fulfill their commitments on time. Because these are large poultry integrators, each of our buyer's suppliers will source product from 2-4 different processing plants within the company but because our buyer only buys the tender, each of those processing plants has to balance their other customers who buy the rest of the bird.

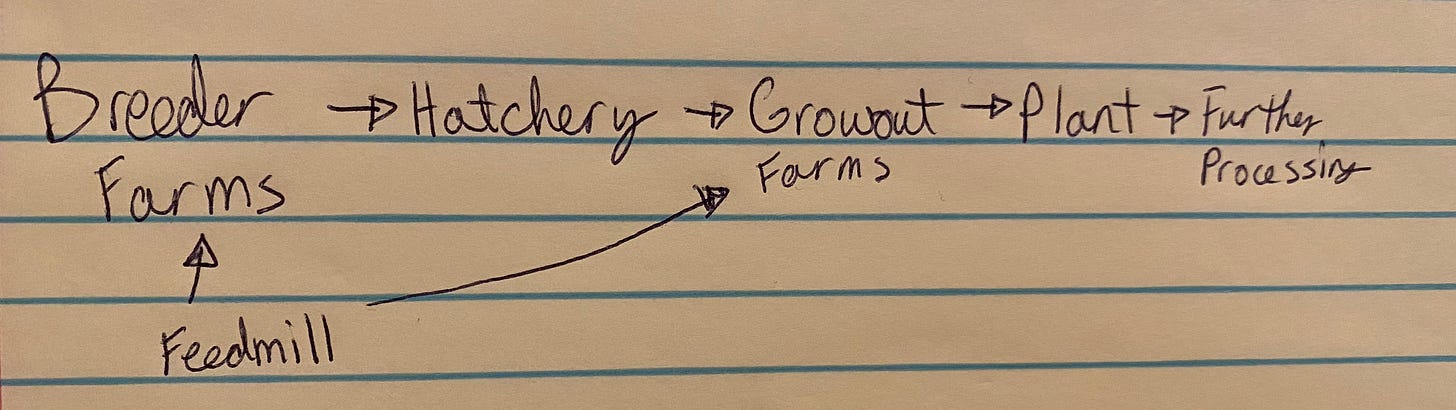

Two truths about the poultry supply chain (pictured here):

Things have to move.For meat & milk supply chains to work, trucking capacity is an existential necessity at multiple points. Every arrow above represents the movement of one physical thing from one step in the supply chain to the next (eggs, chicks, feed, birds, meat). Until localized bullet trains for birds get built, this trucking thing is a big deal.Things have to move on time.Every step in a supply chain with live animals has its own 'turkey timer' so to speak. Chicks have to come out of the hatchery once they hatch and they have to go to a farm, they can’t hang out in the chick trays at the hatchery. Placement numbers in a broiler house are calculated based on density targets by the end of the flock, so birds have to leave the farm at a certain time which means they have to be processed within a very tight window. And once the birds are processed, fresh meat has to move or else it has to be frozen which is a value destroyer. Everything has to happen on time in order for the supply chain to work.

Ford pickups and John Deere tractors can be parked while manufacturers wait on chips to arrive from Taiwan before being shipped to customers in Iowa, but live animals (or milk) can’t be parked in the side lot for days or weeks.

The buyer at Love Me Tenders is reliant on so many supply chain elements to go right, the vast majority being out of the buyer’s control. Which should mean the buyer is signaling to management that we probbbbably need to create some additional back ups for our additional back up plans that were busted to bits over the last 18 months.

The idea of supply chain resilience is everywhere, “the capacity of a supply chain to persist, adapt, or transform in the face of change.” But supply chain leaders will tell you that being prepared for any contingency has always been a core objective, tho perhaps the degree of ‘change’ to be prepared for is increasing in scope/severity.

We’ll continue exploring the complexity around supply chains & the current chaos over the next few weeks but needless to say, there are no easy answers for the Love Me Tenders of the world…or anyone else in meat, poultry & milk supply chains.

I'm guessing 83% of Prime Future readers know more about supply chains than I do, feel free to share some insights:

Have you subscribed to Software is Feeding the World?

If the title alone doesn’t get you, Rhishi Pithe brings a unique perspective to ag. Rhishi describes it as “a weekly newsletter for Food/AgTech leaders about technology trends. The newsletter explores how software, technology, automation, robotics, and data can transform the food and agriculture systems of the future.” 10/10 recommend. (link)

I’m interested in all things technology, innovation, and every element of the animal protein value chain. I grew up on a farm in Arizona, spent my early career with Elanco, Cargill, & McDonald’s before moving into the world of AgTech & early stage companies.

I’m currently on the Merck Animal Health Ventures team. Prime Future is where I learn out loud. It represents my personal views only, which are subject to change…’strong convictions, loosely held’.

Thanks for being here,

Janette Barnard