SPACs: a linchpin for AgTech?

Prime Future 51: the newsletter highlighting trends in livestock & meat

Two recent announcements about late stage AgTech companies merging with SPACs piqued my curiosity about what this phenomenon means for the broader ecosystem. Are SPACs a bubble inducing financial fad or the linchpin to drive more innovation in AgTech?

I admit that I started out with the impression that SPAC is just a fun word to say and that SPAC mania is just a manifestation of a hot stock market, maybe even something we'd point at after a bubble busting event as part of the problem.

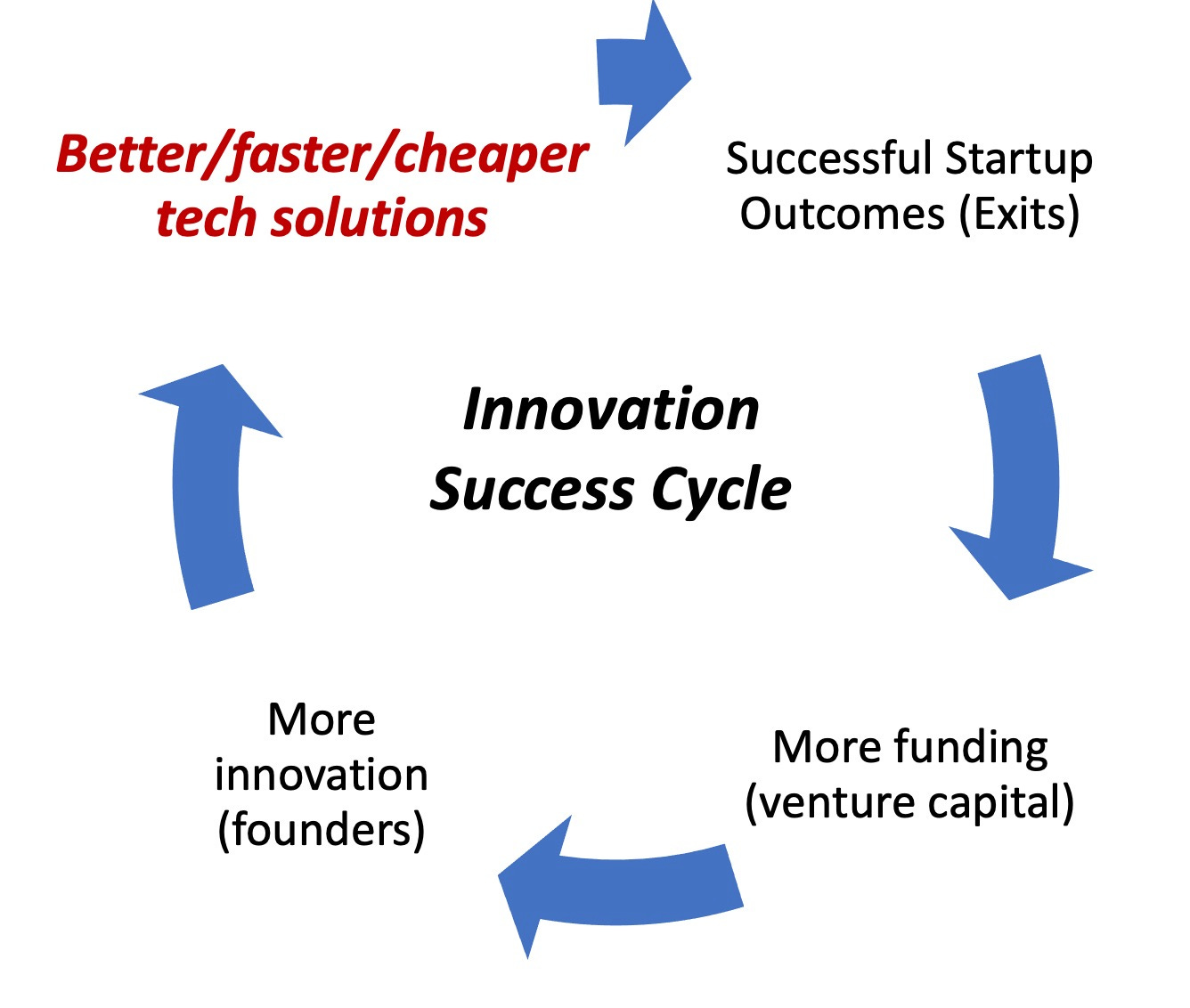

You might be asking, what do SPACs have to do with feed conversion and yield and the day to day of meat & milk production? Zero. Maybe less than zero. But before we dig into SPACs, let’s ground ourselves on the “Innovation Success Cycle” and how the robustness of the Animal AgTech startup ecosystem does impact swine producers and poultry processors and cattle feedyards and errrybody in between:

Most segments can point to a cornerstone acquisition that sparked a frenzy of investment & innovation in a space, on the crop side of AgTech it was Monsanto's acquisition of Climate Corp, that kicked off a virtuous Innovation Success Cycle. The things that increase the velocity at which that cycle spins, and spits out better/faster/cheaper tech solutions, are relevant for those interested in outcomes for livestock producers.

To learn about SPACs I reached out to some AgTech investors and to Will Bunker, the founder of Match.com turned tech investor who is now involved in a SPAC that went public earlier this year and currently securing a tech company to merge.

Let’s start at the beginning, what is a SPAC?

Investopedia: “A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a company with no commercial operations that is formed strictly to raise capital through an initial public offering for the purpose of acquiring an existing company. Also known as "blank check companies," SPACs have been around for decades. In recent years, they've become more popular, attracting big-name underwriters and investors and raising a record amount of IPO money in 2019 and 2020."

Start throwing words around like "blank check companies" and (naturally) people tend to get extremely greedy or extremely cautious. What are the checks & balances on SPACs?

Here’s my understanding: the SPAC itself raises $$ in an IPO based on a thesis of finding an operating company to merge with. The thesis can be geographical, vertical specific, size of company, etc. Then the SPAC looks at target companies that fit their thesis criteria, and then strike a merger deal with the target company. The last step might be most important: the PIPE investors reality check the valuation of the target company - this is the brake that keeps the process from running amok.

According to Will, "The big misunderstanding with founders is they act like a SPAC is another round of financing and therefore your negotiating with a counter party when talking with the SPAC, but it doesn't work that way. A SPAC is a vessel, the counter party are the PIPE (PIPE = private investment in public equity) investors. PIPE investors are the institutional investors that give credibility to the valuation of the company being merged with the SPAC."

So why now? If SPACs have been around for a while, why was there only 1 in 2019 with $13.6B invested and 248 in 2020 with over $83B invested?

Will explained why SPACs are gaining steam and, in his view, very much here to stay:

"Amazon went public in 1997 with a $480M market cap. Today if a tech company wants to IPO they need to have a $20B+ valuation. The effect of the dot com blow up was that the bar was raised for companies looking to go public, so now there are ~6k fewer public companies than in 2000. The whole ecosystem shrank as businesses were bought and consolidated.

We've had 20 years of startups having to wait until they get to $20B+ to go public, which is a hurdle few companies can hit.So why are more SPACs happening now? It's a social thing - SPAC used to be a 4 letter word. It's like the fable of the fox and the grapes - the fox can't get to the grapes so he finally says he doesn't want the grapes. Tech companies struggled to get to the scale necessary to go public after the dot com bust, so they finally said ‘well being a public company stinks and I don't want to do it anyway.’”

“Tech companies convinced themselves they didn't want to go public because they couldn't. Now that’s changing.”

At this point the skeptic is thinking, “why are SPACs popular now? Silly question, look at the stock market over the last 12 months….the answer is obvious.” But Will’s explanation highlights that the timing of SPACs is an entirely separate question from the purpose of SPACs. He specifically said “Founders have to control what they can control which are the things a multiple is multiplied by (e.g. revenue or EBITDA) because you can’t control the market. Will SPACs be abused? Yes, there will be idiots who take companies out that don't have a business model. But if you are taking a legitimate business that has a business model and is on a growth path, this path is as legit as it gets.”

But what's the point of SPACs? Why would a startup take this path to public markets instead of an IPO or direct listing, or even staying private longer?

On this Will said:

"Once your company is public then you have currency to buy companies: stock. As a private company making acquisitions with equity, you give so much of your company away so acquisitions are less common. There are 3 things you can do in public markets that you cannot do in private capital markets: borrow without personal guarantee, issue secondary shares to raise capital, make acquisitions with shares.

If you want to build a big company, a SPAC lets you access public markets at a valuation that is a step function below what you had to wait for otherwise. Instead of waiting until $20B valuation to go public, our analysis is that post-merger valuation (Enterprise Value + new cash) should be greater than $500M so that you can get coverage from analysts and the stock price will increase as you execute. You don't want to be a micro cap, so probably the smallest would be $300M EV + $200M cash.

Valuations come from comps. Founders looking at a SPAC should know who they will be compared to in the public market and work backwards to figure out what you need to do to increase enterprise value. Companies that go public via a SPAC should then be able to be acquisitive, they should become the strategic, and do the consolidating and expanding in their space. If your outcome is build a big co, these tools can help you build a bigger company faster and this is a path to do it. ”

What are the implications of SPACs on the AgTech startup ecosystem?

The partners from Fulcrum Global Capital, an agtech venture firm, put it this way when asked what the implications are for AgTech: “Huge! With pressure for innovation building across the industry for years and established strategics focused on consolidation, there has been a notable lack of exits within the agtech industry. SPACS offer an outlet for a subset of companies with the right combination of transformative technology and growth potential. And obviously, successful market entry by those early SPACS can breed a larger appetite in both the public and private markets, thereby making the entire industry more attractive from a risk capital perspective, which should lead to a more rapid technological development across the entire industry.”

So there it is: If SPACs allow startups to access public capital markets earlier in the company’s life than a traditional IPO, then the company has greater access to capital for growth, like acquisitions.

And more acquisitions and more risk capital in a segment lead to more investment and innovation which leads to better/faster/cheaper solutions for customers.

When asked if SPACS are here to stay, the Fulcrum parters said this, “Obviously, the strong economic climate coupled with a more environmentally-focused current political environment are favorable for the current round of SPACs hitting the markets. That said, ultimately the answer will likely be based on how the early movers perform on the public markets. If those companies deliver on the promise they currently hold, the market will likely be receptive in the future.”

Will sees the potential impact of SPACs for founders through a very personal lens, "We sold match.com to Barry Diller who then spun it out for $15B and its now trading at a $45B market cap. If this had been a tool when I was a founder, I would have captured so much more of the value of my idea and more of the value would have gone into my pockets than someone else's."

And because who doesn’t love a good example of supply & demand at work, Will shared this gem: “SPACs are like penguins - I'm a beautiful penguin and I'm special but no one else can tell the difference. The financial press is saying we've never seen so many penguins in our life! But on the flip side there's such a backlog of companies looking for 'penguins' to help them go public that there’s an imbalance."

Back to our industry of interest, of the 4 AgTech companies who’ve either merged or announced a merger with a SPAC, not one has a footprint in Animal AgTech. But that’s not surprising as there aren’t many (any) late stage startups in this space. As we've talked about before, animal agtech lags crop agtech in terms of total investment and venture backed startups which, related, many VC’s attribute to fewer active acquirers on the animal side.

So let’s say that a few animal agtech startups go public via SPACs in the next 3-7 years and that creates more acquirers for animal agtech startups over the subsequent 3-7 years….that’s still, umm, quite a while before any potential impact of SPACs would be felt in the animal agtech ecosystem.

The point is that SPACs could maybe, definitely, possibly be a potential catalyst of innovation in livestock in the long run.

Will it be a linchpin tho? WAY too early to say.

Prime Future Summary

You can get the first 47 editions of Prime Future in 1 PDF here, check it out:

Hit reply on this email

In the book Effortless, Greg McKeown talks about the idea of “inverting assumptions” to highlight new ways of doing things, solving problems, etc. I’ve been thinking about this exercise as it relates to the deeply held convictions within livestock production and how those assumptions impact all things innovation. So, here’s my question:

What is one assumption that has been generally accepted as true within livestock production & processing, that is not true / no longer true?

Hit that reply button and make your case. 😁 And stay tuned for more on this...

I'm on the Merck Animal Health Ventures team. This newsletter is not representative of anyone's views but my own. Sometimes it doesn’t even represent my views :)