The packers get Standard Oil'd. Then what?

Prime Future 57: the newsletter for innovators in livestock, meat, and dairy

This is neither political commentary or prediction. This is a look at the hypothetical implications of a hypothetical scenario that has a zero percent chance of happening.

If an oligopoly market is when 4 firms have 50+ percent share, then US beef, pork, and poultry are undeniable oligopolies. These concentrated markets aren’t uncommon though, we run into them from cereal (Kellogg’s, General Mills, Post, and Quaker) to cell phones (Apple, Samsung, Huawei).

But these examples are child’s play compared to the most extreme example of market power: the classic story of Standard Oil. In the 1880’s, John D. Rockefeller realized the oil business was a fantastic business except for the nagging issue of price volatility. So he found a solution to that little problem, by developing an effective monopoly through the Standard Oil trust. A Supreme Court ruling in 1911 forced the trust to split into 34 companies to increase market competition.

The current rally cry of many US producers is that the problem with the cattle business is concentration among the packers. This is not new; tale as old as time. But carry that rally cry out to the most extreme outcome of de-concentrating processing capacity….what does it really solve?

Just for fun, let's say the DOJ goes full 1911 and ‘Standard Oils’ the meat industry.

Every plant becomes its own company.

The ‘Big 4’ become the ‘Midsize 22’.

Then what? Before we lock into any hypotheses about a re-fragmented meat industry, what was the result of busting the Standard Oil trust?

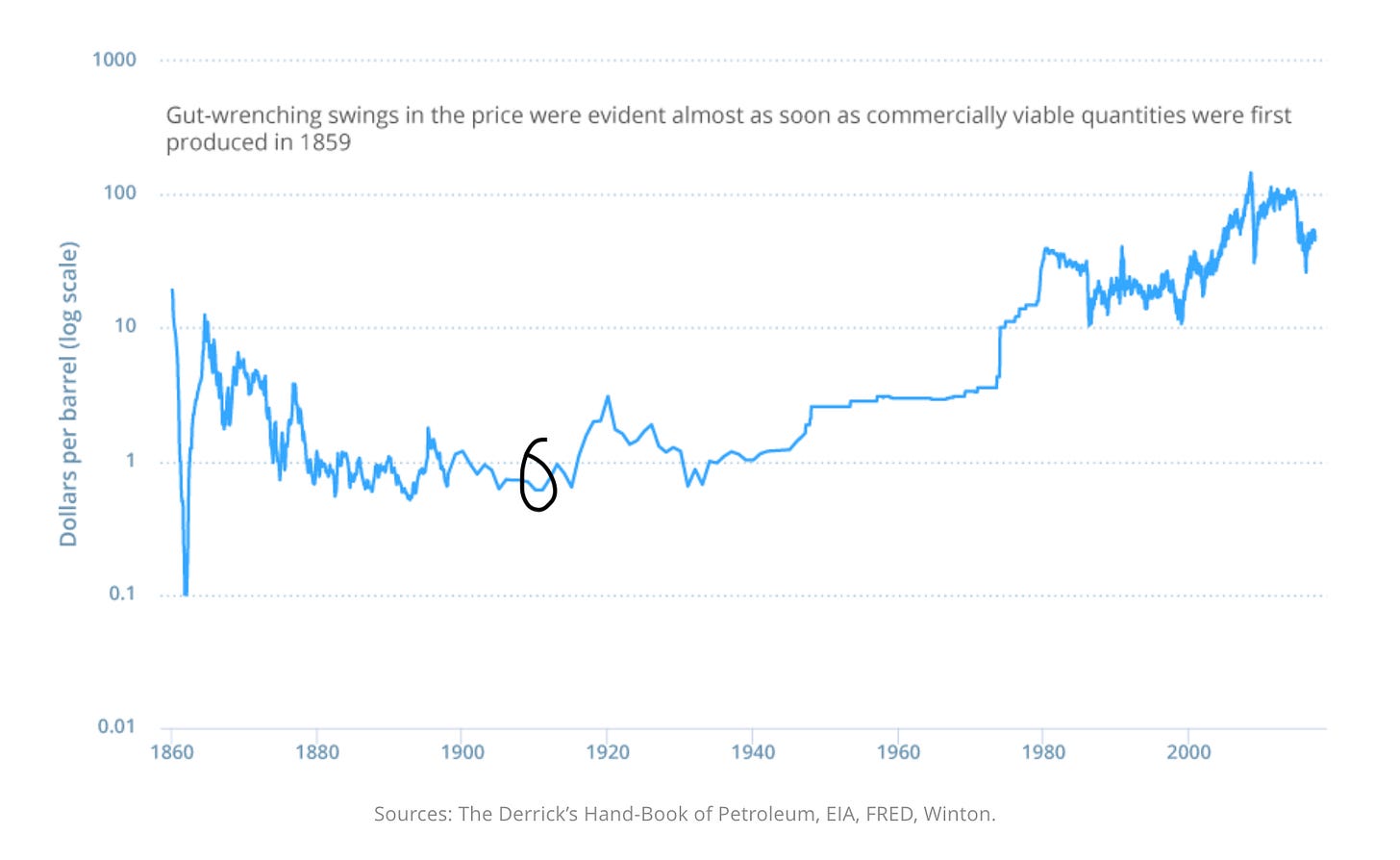

Keep in mind that also around 1911 the rise in automobiles meant gasoline (previously a worthless byproduct) was suddenly worth more than kerosene, and that other regions of the world began producing oil competitively so the entire oil market was shifting as Standard Oil was split. Here’s a snapshot of oil prices before and after:

So the Standard Oil trust was busted and then prices went…up? While there are clearly more factors at play than we’ll dig into here, my takeaway from this chart is that this whole scenario is not as straight forward as anyone would like it to be. There are a lot of factors at play; markets are dynamic and impacted by all the things from pandemics to stimulus programs to weather.

The livestock & meat industry’s common hypothesis is that if the packers were less concentrated, then market power would ‘return’ to feedyards & producers upstream and downstream customers in foodservice/retail. It would ‘free up margin’ by taking away the packer’s pricing power on the buy and sell side. Econ 101.

But is reality as clean as an econ textbook? Are we *certain* that the net effect of increasing packer competition would definitively be positive for the rest of the value chain?

The 2 dimensions I’m interested in are price (purchasing live cattle, selling boxed beef) and innovation (finding new ways to better serve customers & end consumers).

Let’s start with downstream. What would the implications be for further processors, retailers, foodservice, and end consumers?

Price: Packers sell to further processors, distributors, retail and foodservice…segments that also happen to be highly concentrated. Let's say a national retailer like Walmart who sells ~20% of US retail beef today buys from 1 or 2 companies. Each supplier has multiple plants that service multiple Walmart distribution centers with multiple SKU's at tailored specs. Plants have become specialized with specific programs or specific customers. The big processors were able to flex reasonably well as COVID shut down foodservice because of diversification of channels across plants - individual plants didn’t have that diversification.

In a Standard Oil trust busted world, is a national retailer now going to work with 10 independent plants that are each independent suppliers? What does that do the retailers ability to keep meat cases full with homogenous supply of fresh meat at spec? Big companies like to deal with big companies that can handle big business. What does that increased friction in the whole process do to the price of meat at retail? On the other hand, what would increased competition among packers do to the price of meat for retailers?

Innovation: A key rationale for minimizing oligopoly or monopoly markets is that competition leads to innovation. Agree, of course. But you know what else leads to innovation? Resources. What is the optimal mix of incentive to innovate and resources to innovate as a function of market power? I don't know. But low margin businesses without scale don't tend to be fountains of innovation.

Innovation = Incentive + Resources

Then let’s look upstream. What would the implications be for cow-calf producers and feedyards?

Price:Cow-calf producers don’t sell to packers, they sell to sale barns or stockers or feedyards. The feed yard space is way less concentrated than processing but way more concentrated than cow-calf. Say feedyards have more pricing power if packers are split up….does that trickle up to cow-calf producers or does it just mean feedyards are the new margin sinkhole of the beef supply chain?Innovation:Let’s say more of the total value chain margin stays upstream. Maybe that leaves some financial wiggle room to focus on things besides survival So do producers start thinking about things consumers are talking about like carbon footprint? I don’t think so. Not unless the incentive structure changes and packers pay more to feedyards who pay more for calves that are raised a certain way at the cow-calf operation.

A complicating factor is that even if you increase processing competition nationally, it does not necessarily mean you increase competition regionally.

And if packers cannot consolidate processing capacity, would the result be more vertical integration in an attempt to consolidate supply chain control?

An obvious factor that makes meat processing different from cereal is that it’s a capital intensive business so barriers to entry are high, really high. It's an economies of scale business, so it’s a business that 'wants' to be consolidated to chase more economies of scale.

But even if the US government regulated away processor’s ability to consolidate, what would that mean for the US industry's ability to compete against emerging regions? The world’s largest hog farm was recently built in China for 84,000 sows to produce 2.1 million hogs annually….wouldn’t it stand to reason that the world’s largest processing plant(s) will soon follow?

Would a Standard Oil'ing of meat packing be good for downstream players? Maybe, in the short run. Probably not in the long run.

Would a Standard Oil'ing of meat packing be good for upstream players? Maybe, in the short run.

But what’s not good for downstream players in the long run cannot be good for upstream players in the long run.

Hear me loud & clear that profitability at all stages of the value chain is the #1 foundation of a viable cattle industry. Increasing margin capture throughout the value chain is a good thing, a great thing. But is reducing packer power the panacea that people often describe it as? I may be wrong, but I just don’t think it is.

Maybe looking at impact of competition on pricing power & innovation is the wrong framework….maybe higher margins don’t lead to innovation, maybe innovation leads to higher margins.

Are oligopolies good or bad? Should the big 4 be broken up? Irrelevant questions.

The actionable question is, how do you win when you buy from or sell to an oligopoly marketplace? Control the control-ables and innovate the innovate-able.

At the end of the day, animal protein is a commodity driven business. And what do commodity markets do? They move in cycles. Sometimes tree growers profit, sometimes lumber mills profit. Sometimes the cow-calf producer wins, sometimes the packer wins. Sometimes dairy producers make hand over fist, sometimes processors do. Sometimes oil drillers print money, sometimes refineries do.

‘your margin is our opportunity’

Look at other industries where big companies in one segment of a value chain amassed market share and then stopped innovating. Think IBM in the 80’s. You know what happened when those companies got satisfied with their market share and stopped innovating? Apple. Microsoft. Dell. A resurgence of insurgents jumped in with new innovation that captured market share…and then those ‘new’ tech companies get big and face their own anti-trust scrutiny. It’s almost like everything is a cycle and the cycle is what creates opportunity…

You could easily argue that type of insurgency is what upstarts like Cooks Venture or Shenandoah Valley Organic could be in the US poultry business.

Carl Lippert recently summed this up well in his article The Farm Barbell,

“The future of agriculture is large farms producing commodities and small farms creating value added products."

That's true for producers AND for processors.

The only way to stay in a commodity driven business AND get out of the trappings of commodity cycles is to build a competitive moat, to pursue value added markets. That's also true for producers AND for processors. We’ve talked about this before:

The livestock & poultry industry has spent decades driving cost out of animal production systems to increase profit. And we’ve done it well. Really well. More pounds per animal. Less feed per pound of gain. Least cost feed formulation. Increased efficiency.

And yet, we see record high number of farm bankruptcies, near record low farm income, and volatile train wrecks of milk, live cattle and hog markets the last 6 months. All of which point to revenue challenges in animal agriculture.

Commodity production is an existence governed by a ruthlessly brutal dictator: The Market. It’s time to focus on enabling livestock producers to increase Revenue, to escape the commodity game that’s ruled the industry, to differentiate.

The punchline of Lippert’s article sums up the implications of this whole discussion for startups in animal ag:

“Startups should build penny shaving machines for scaled farms and margin capture machines for small farms.”

Yes.

(For more on the Standard Oil saga, I highly recommend the book Titan by Ron Chernow.)

Livestock Market Transparency is Possible. Here’s how. (link)

On a related note, this piece was written at the height of 2020’s chaos:

Pricing is a hot topic in light of live cattle and boxed beef prices heading in opposite directions, and the same dynamic to a lesser extreme in pork. These pandemic market dynamics highlight the need for improved price discovery and market transparency across the entire meat, poultry, and livestock sector. These are great problems for technology to solve. Here’s why: (link)

Prime Future is a weekly newsletter that allows me to learn out loud. I'm on the Merck Animal Health Ventures team. Prime Future represents my personal views only.