"the rain follows the plow"

Prime Future 119: the newsletter for innovators in livestock, meat, and dairy

The Dust Bowl was one of the most economically and ecologically devastating times in American history. Millions of people abandoned homes, farms, and family to escape the terrifying dust storms and their wreckage.

It was the deadly combination of drought, economic depression, and extreme dust storms that destroyed the finances, health, and morale of an entire region. Imagine wearing a mask 24/7 during severe dust storms that lasted several days, including in your home, to reduce the risk of dust pneumonia. Imagine going out to check cattle and finding a few more each time that had suffocated…from dirt.

It wasn’t just farmers that were wiped out, entire communities were decimated.

I've read a decent amount about how gut-wrenching life was for people who lived through the Dust Bowl but only recently watched the Ken Burns documentary which highlights the economic context around the Dust Bowl.

The Dust Bowl followed a time of never-before-seen economic prosperity, during and after World War 1: the roaring 20's.

Meanwhile, the innovation of all innovations was rapidly changing the agricultural economy: the tractor. The tractor enabled American farmers to cultivate more acres, primarily wheat.

With the global economy soaring, wheat exports were soaring and with it, wheat prices.

Keep in mind the 1920's were less than 40 years since buffalo had been cleared from the Plains, and less than 20 years since the last cattle drives through the midsection of the country. The Plains were still largely a grassland & grazing ecosystem…until the tractor came along.

And wheat was less than 15 years old as a primary commodity across the heartland of the US. Commercial-scale farming across the plains was still a relatively new experiment; wheat as a cash crop was still a relatively new experiment.

As the price of wheat went up, so did the number of acres plowed to supply what seemed like insatiable global demand. This happened rapidly as 11 million additional acres were plowed within 5 years.

Because the law of supply and demand is immutable, wheat prices dropped as wheat production exploded.

As the price of wheat dropped, farmers plowed more acres to make up for lost revenue.

Meanwhile, the broader economy was feeling the weight of the Great Depression. Wheat prices dropped further.

And somewhere in the midst of that decrease in demand and increase in supply, a severe drought hit the center of the country and settled in.

But that wasn't supposed to happen.

The prevailing mantra of the era was, "the rain follows the plow".

In 1933, the same year there were 38 multi-day dust storms that ravaged Oklahoma and surrounding areas, along with crop-stopping drought.

Of course, we know that "the rain follows the plow" was a laughably incorrect notion, it was wishful thinking at best.

So, why is a newsletter written for forward-looking innovators digging up 100-year-old history?

Because I believe, like much of history, there is a lesson in the Dust Bowl.

The lesson is this: no matter how much we think we know, we need a heaping dose of humility when it comes to nature and our collective understanding of nature’s systems and complexities.

There's all that We Know We Don't Know. Think of how limited our understanding is in many areas of science from the human brain to soil health to human & animal microbiomes.

Then there's all that We Don't Know We Don't Know.

But perhaps most humbling, are all the things We Think We Know That Are Yet To Be Proven Wrong.

Like folks in the 1920's plowing up ground with the confidence of "the rain follows the plow" and the confidence that wheat prices would continue up and to the right. In hindsight and with modern meteorology and agronomy, we know that idea couldn't have been more wrong.

It's easy to think how much smarter we are as a society today but I have to assume there are things that we accept as true today that in 100 years, society will laugh at how silly we were for believing some things.

We have to be curious in the face of nature’s complexity, as curious as we are convicted about the things we think we know.

This becomes really practical really quickly when it comes to topics like climate change and regenerative agriculture…and relevant for all sides of these debates where conviction tends to run really high.

And yet, what’s old is new…

I recently found this photo of my grandmother from 1946. She grew up in southwest Oklahoma, on a crop and livestock farm. (My great-grandfather was known as a lunatic farmer for all the innovative things he did while farming. Yes, his name was Prime and yes, the name of this newsletter is a hat tip to him💙.)

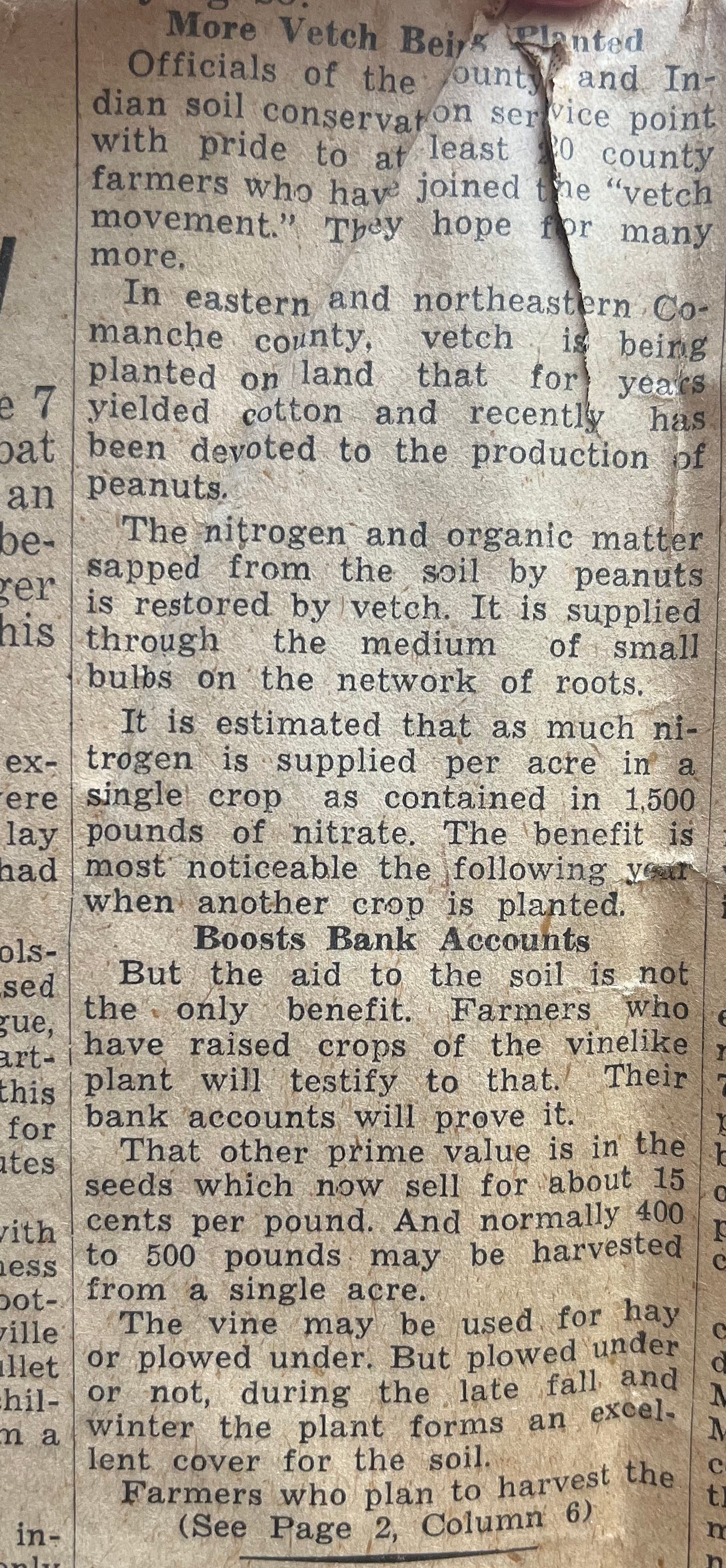

One of the lunatic things he did was early adoption of cover crops to promote soil health, including vetch. The newspaper clipping went on with ideas that are now very familiar:

Shane Thomas of Upstream Ag Insights recently wrote a fantastic piece, Regenerative agriculture doesn't have to be contentious:

What is a better approach in my mind is to break down “regenerative ag” into its component parts and seek to better understand each of them and where a farmer can implement small changes by field or farm vs. wholesale telling farmers to “be regenerative” when what regenerative is a bundled system of practices.

It’s worth remembering, a broke farmer is unlikely to be a regenerative farmer. Some practices, like say fall seeded cover crops need to be assessed in the context of the most limiting factor to produce a profitable crop too: if rain is a significant constraint, that might not be the place to start!

This is the benefit of breaking things down into their components: it changes the discussion from an “all or nothing” conversation to a “here’s a starting point and basic roadmap” which is much more palatable for everyone involved.

The problem is that these topics can easily turn from hypotheses with nuanced complexity, to oversimplified & unexamined dogma.

To say regenerative is the answer without a clear definition of what regenerative agriculture is or how it’s measured, is as misguided as saying regenerative is not the answer even though most farmers utilize at least some regenerative practices.

To Shane’s point, even in 1946, cover crops were one example of many practices identified as good for the soil AND good for the bottom line, in certain contexts.

So, here's to curiosity. Here's to learning. But just as importantly, here’s to being able to un-learn when that’s what the moment calls for.

Because the rain definitely does not follow the plow.