Lunatic farmers, velocity, & the 1% rule 🚀

Prime Future 107: the newsletter for innovators in livestock, meat, and dairy

The content below is from one of my favorite Prime Future editions from 2021. In the coming months, we’ll build on the concept of the lunatic farmer and how they give us glimpses into the future.

But as you read about lunatic farmers & the idea of business model velocity, keep in mind these words from James Clear:

It is so easy to overestimate the importance of one defining moment and underestimate the value of making small improvements on a daily basis. Too often, we convince ourselves that massive success requires massive action.

Meanwhile, improving by 1 percent isn’t particularly notable—sometimes it isn’t even noticeable—but it can be far more meaningful, especially in the long run. The difference a tiny improvement can make over time is astounding. What starts as a small win or a minor setback accumulates into something much more.

Now imagine how this 1% compounds over a 40-year career or over 5 generations of a family business or over 100+ years of industry evolution…so much lunacy.

Oh and if the context clues so far weren’t enough, “lunatic farmer” is my highest and best praise, a term of endearing admiration and total respect.

The owner of a dairy was lamenting the rise of mega dairy systems and the risks they pose to small dairies like hers. How many cows does her dairy milk?

7,000

It's a laughable story except that this dairy farmer & her family have grown the herd from a few hundred to several thousand over the course of their career. They've struggled and strived, taken risk after risk to get where they are. And yet in their minds, they still identify as small, scrappy, insurgent producers trying to survive.

There's a dynamic that plays out across the ecosystem of food production where size matters. To everyone. A lot. There's an awareness (obsession?) about the size of suppliers, customers, processors, and neighboring operations:

Big retailers want to deal with big food brands, not small insurgents. There are tangible costs to dealing with more suppliers, it smaller suppliers, inexperienced suppliers with unproven track records, etc.

Some consumers want to buy food produced on a 'small family farm', whatever that means. (Why does 'family' have to imply a modest-sized business? And who decides what size is the right size? And don't *all* small businesses either evolve, grow, or die? I digress…)

Some (most?) producers would like to sell livestock to small(er) processors who have less pricing power than processors in an oligopoly have. (What if the packers got Standard Oil’d?)

Many producers fantasize about having more acres, or head of cattle, or poultry & hog barns.

There’s a special irony in the tendency among farmers to want to be bigger than neighboring operations. It’s almost a tendency to criticize the operators who run more acres or head than they do. (But is it criticism or envy? Sometimes the two look eerily similar.) It's like a Russian nesting doll situation where the 700 acre farmer judges the 2,000 acre farmer who criticizes the 15,000 acre farmer as too big. I’ve heard this lament from midsize farmers a few times recently and it raises some questions…How many acres is too big? How much profit per acre is too much? How much revenue per year is deemed over the top? These sound like questions that supporters of alternative economic structures would ask, not those who enjoy the benefits of a capitalistic economy….

The primary counter to the notion that small business > big is the idea of available resources. Who is in a position to commit more resources to ensuring appropriate nutrition - the backyard poultry farmer or the large integrator? Who is in a position to invest in technology that reduces deboning costs in the plant - the custom processor killing 50 head/day or the large plant killing 5,000 head/day?

The primary counter to the notion big business > small is, well, we just know this isn’t always true, right?

Big business can be good, small business can be bad. Vice versa. Some small businesses are amazing employers, some are terrible. Some small businesses are terrible suppliers, some big businesses are amazing customers. Vice versa.

I’m less intrigued by the external voices extolling or incriminating business size. I’m more intrigued by the view of producers, and what causes some producers to maintain status quo and some to find a model that allows them to scale.

Sometimes bigger is better, sometimes smaller is better…size is not the indicator of success and it’s definitely not the goal.

A recent Reddit thread on personal finance included a comment by a couple making $500,000/year who un-ironically identified themselves as a middle class family with middle class money concerns. It’s a similar dynamic with the large producer who still has the mentality of scrappy insurgent, maybe (likely?) that mentality is what helped them get where they are - what helped them do things their peers weren’t doing, to get different outcomes than ‘average’ producers.

Can we just admit that the obsession with farm business size is....kinda odd? Or at a minimum, it's not very helpful.

My hypothesis is that scale is a lagging indicator; velocity of business model innovation is the leading indicator of success.

The more commoditized the business, the stronger the pull to scale to reduce cost per unit. The more value oriented the business, the stronger the pull to create incrementally more value per unit. There's no clever analysis in those statements - those are natural forces that are a function of capitalism and a mature agriculture industry.

I think the successful producers (or packers or xyz business) who will thrive come-what-may are the ones who don’t think of their business based solely in terms of the output (corn, soy, weaned calves, whatever), but rather view their business as a business model that is in continual refinement mode. They constantly ask what's the process that most effectively generates the output. They think in systems that can optimized.

(This is a great article on the founders of Premium Standard Farms, the ‘inventors’ of the mega farm / consolidation model in pig production and the mental models they put to work…some worked, some didn’t. Btw I’m still waiting for a good book about this phenomenon in poultry - can somebody write that plz? 🙂)

It seems that the really successful producers are the ones that have a vision of where they are going and how they will get there. There's no doing it this way because that's how we've done it, there's no growth for the sake of the growth. There is only relentless learning and improvement.

The great producers realize that they aren't selling just a commodity output, they are selling their business model.

Size is not the determinant of success. It’s about business discipline, management, relationships, processes, team, leadership, ambition. Successful producers have a vision for the future that they rally the team around, there's an ever-evolving plan for increasing revenue per unit produced or decreasing cost per unit produced, or both.

I recently asked a really large operator how they grew their business over the last 20 years from something not at all uncommon to something truly extraordinary. Did they have access to capital that others didn't have? Some other advantage not available to similar producers? "I don't think so, I think we just do things in a different way than most people are interested in doing. We do a lot of things that aren’t uncommon for most growing businesses, they are just uncommon for production ag businesses. We have a yearning for learning. "

Let’s call a spade a spade - capital is abundant and cheap in 2021, as it has been the last several years. Ideas are a dime a dozen. It's everything else that separates the aggressive producers from the rest. (The rebuttal I’m expecting is what about the market, the weather, etc etc etc…..luck and timing play huge roles in ag, I’ll never downplay that. But there’s more to this phenomenon than that.)

I've referenced Allen Nation's book before, but germane to this conversation is a chapter on how farmers approach innovation with insights pulled from a 1962 book "Diffusion of Innovation" that studied extension efforts to get farmers to switch from open pollinated to hybrid corn post WW2.

"

The innovative farmer is seen by his farm neighbors as a lunatic farmer.And a lunatic is not seen as a role model. As a result, what the innovator does on his/her farm is literally invisible to the neighbors. This is true even if the innovation is producing visible wealth. The normal reaction to unconventional success is the old it-might-work-there-but-not-here syndrome. The sad truth is that the vast majority of farmers prefer to fail conventionally rather than to succeed unconventionally. It is very, very difficult to be more innovative than the community in which you live.

Here's the really germane part: "No farmer referenced what a farmer smaller in acreage than themselves was doing as applicable or worthy of study. Everyone preferred to learn from someone larger than themselves." Isn't that fascinating?

There’s irony in that if you’ve made it this far, then there’s a huge chance that you are in the groups referenced in this last quote from Allen Nation:

"The innovators and the early adopters form approximately 15% of the total farming community. Interestingly this percentage is almost exactly the same as the number of farmers who earn an upper class income from agriculture."

I’ve recently observed some markers that lunatic farmers seem to have that indicate high velocity of business model innovation:

They ask questions. A lot of questions. They find smart people to ask questions. They find smart people in non-traditional places to ask questions.

They read. Not just industry magazines, they look outside.

They have a sense that what they are saying sounds half crazy, dare I say they know it might make them sound like a lunatic farmer.

They surround themselves with high quality people, high quality teammates.

They have a system they are building/running, a flywheel they are looking to spin faster.

They have some insight that most of their peers don’t, some belief that isn’t widely held.

They know new practices & ideas take time to implement correctly, so they allow margin (time, energy, $) to experiment.

I’ll wrap up today with a tweet:

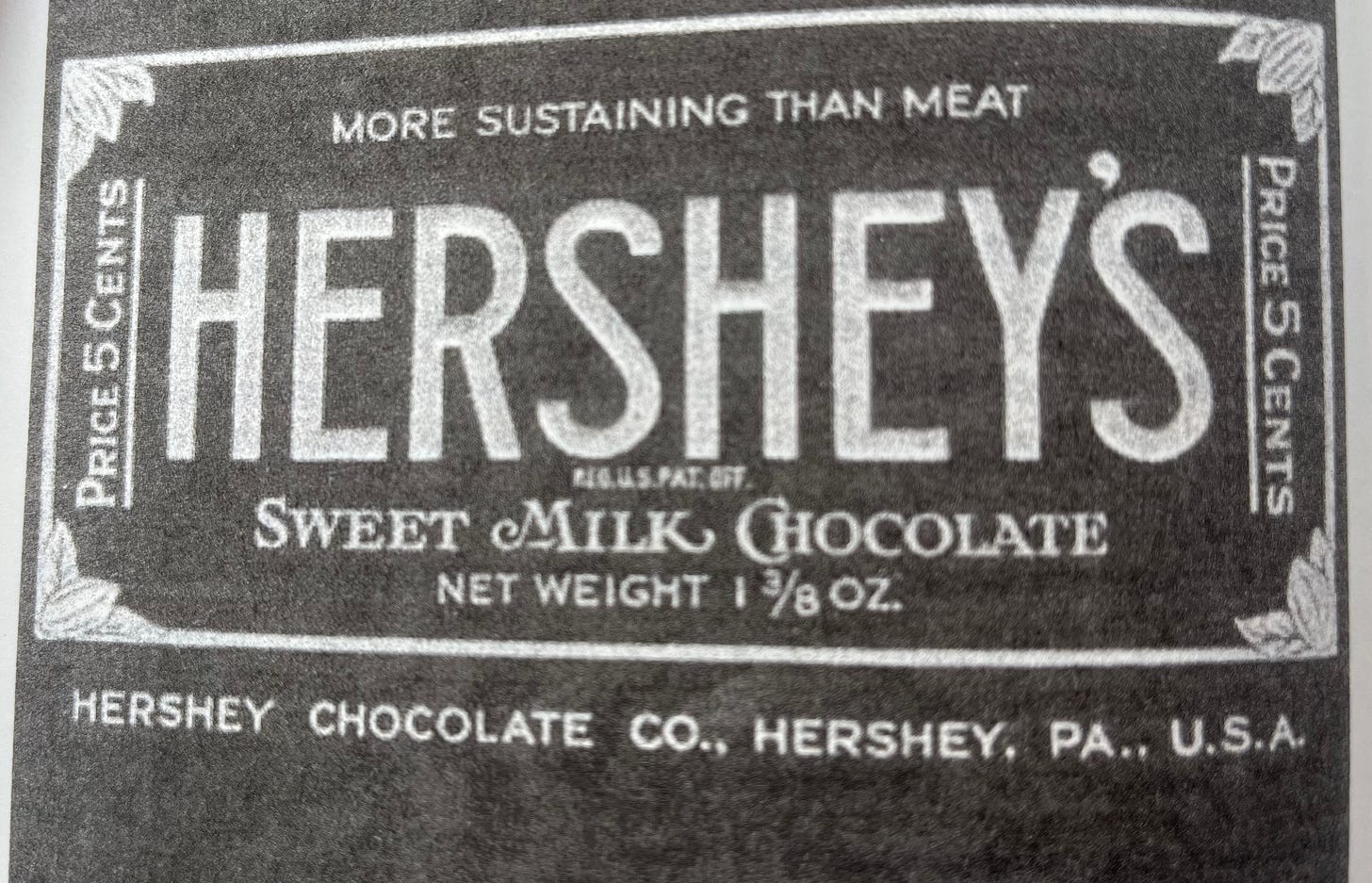

Oh, and here’s a Hershey’s ad that ran from 1906-1926. Food history is stranger than fiction, isn’t it?

Loved this! Curious if Allen went under a pen name? The 1962 book, "Diffusion of Innovation" I can only find referenced under Everett Rodgers. I also know of author Allan Nation who also wrote a lot of books around agriculture finance, but that timeframe was more early 90's - 2010's so that doesn't seem like the same person.